In 2025, various Scottish Councils addressed the need to explore a Visitor Levy – more commonly known as a tourist tax.

Under the draft scheme, overnight guests would pay an additional fee on their accommodation bill.

At first glance, the rationale is simple: visitors use local roads, trails, and services, so they should contribute to their upkeep.

Across Europe, levies fund public toilets in Venice, heritage restoration in Porto, and trail maintenance in the Dolomites.

But the real question for Scotland is not whether to tax, but how the money is spent, who bears the burden and how the money will be redistributed.

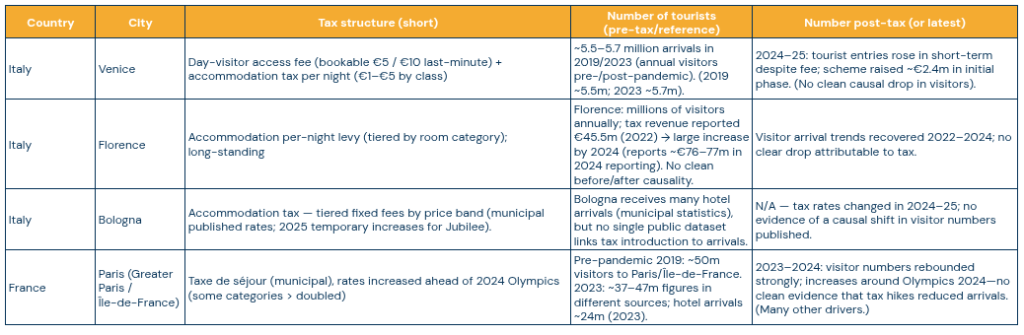

We analysed most of the proposals that local councils put in place, presented and published; apart from a couple of very good examples of an analysis well done, we found that most reports used examples that are simply not suitable for Scottish Councils.

Tourist Taxes around the world

At the moment, it seems that Councils are racing to set rates, caps and collection rules now that Holyrood enabled levies — the pattern we see emerge is:

Cities set percentage levies (Edinburgh 5%, Glasgow 5%, Aberdeen 7%) while mixed/rural councils (Stirling, Highland, Argyll & Bute, Dumfries & Galloway) are still testing options that reflect their different visitor mixes. Cite VisitScotland listing.

However, what is a “tourist tax” and how do cities and countries use it?

There are two common models:

- Accommodation (per-night) levies — charged per person per night (common across Italy, France, many European cities). Revenue is collected through hotels/hosts and remitted to the municipality. These taxes are used for destination promotion, infrastructure, and cleaning/visitor services. Among the cities that chose this model, we find cities of the calibre of Florence and Paris. In 2024, Florence reported a jaw-dropping EUR 76.9 million in tourist taxes that have been used to improve the city’s transport, connection to other Tuscan beauties and conservation efforts. Bologna tried, instead, an overnight tax based on accommodation price band (higher costs for your room equals higher tax) and visit volume to encourage all-year-round tourism.

- Access or day-visitor fees — charged to people who enter a zone but do not stay overnight (recently used in Venice to target day-trippers). These are less common and often targeted temporally (peak days/times) or spatially (historic cores). Among these, the most clamorous case is Venice, which has long charged EUR 5 per day to visitors (EUR 10 per late bookers) and has been able to collect EUR 2.5 million in the trial period itself, yet failing to do any proper crowd management, as the dangerous flocks of tourists that the city experiences in summer are usually called.

A third hybrid is variable or dynamic pricing — higher charges on peak days or for premium rooms and discounts/waivers off-season — which aims to raise revenue and smooth seasonality. Paris has tried this, but the results cannot be compared to the others due to the Olympic Games, which would skew any results.

So far, research on Tourist taxes has failed to address the impact of said taxes on the different types of tourists and, most importantly, on microbusinesses and small businesses.

Our Findings

What we found working with small towns in Italy and Provence in 2025 is that when talking about Tourism Tax we need to think in terms of :

- Negative Displacement: We noticed that flat fees applied to tourists, regardless of their total holiday costs (accommodation, travel, and other expenses), reduce disposable income for discretionary local spending. This is especially sensitive for families, day-trippers, campervan travellers, and Airbnb guests. One issue we identified — though we don’t yet have enough data — is that the size of the negative displacement effect depends on the tax relative to the total trip spend and on visitor elasticity.

- Public Good Multipliers: If tourists feel they have a better experience because of the tax, they are more likely to see it as added value rather than an extra cost. However, the improvements and services funded by the levy must be visible.

So, let’s take a look at the data we have:

Scotland’s Emerging Levy Landscape

The Visitor Levy (Scotland) Act 2024 allows councils to set their own rates, but no scheme is yet in force. Several have announced their plans:

- Edinburgh: 5% levy, starting July 2026

- Glasgow: 5% levy, from January 2027

- Aberdeen: 7% levy, from April 2027

- Stirling, Highland, Argyll & Bute, Dumfries & Galloway: consulting in 2025

Unlike New Zealand’s visitor entry charge or Venice’s €5 day-tripper ticket, Scotland’s model focuses only on overnight stays. That leaves out day-trippers, who are often the majority of visitors in rural and heritage towns.

It is important to understand the different ways in which methodologies and data work when it comes to tourism.

Stirling: A Case Study in Local vs. Central Control

Stirling Council’s proposal is particularly revealing. The 5% levy would apply across the entire council area, from the city itself to towns like Callander and Doune, and into parts of Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park.

- 3% of collections are kept by accommodation providers for admin.

- The remaining 97% goes into a central Council pot for “tourism-related projects.”

What’s missing? No guarantee that funds raised in Callander, Crianlarich, or Balfron will actually stay there. Local businesses fear that rural areas will subsidise city-centre improvements while their own toilets, trails, and car parks remain underfunded.

The analysis undertaken by the Stirling Council used interesting examples from relevant and highly touristic cities, and analysed rural tourism in New Zealand, but Scotland is different. The Council includes, in addition to the City of Stirling, many towns, villages, hamlets and dispersed settlements.

The levy hits small providers in subtle ways:

- Admin costs: Estimates suggest £150–£1,100 in set-up costs and £200–£850 in annual running costs. For a B&B turning over £60,000 a year, that’s up to 2% of annual income gone before the levy is reinvested.

- VAT threshold risk: If a provider near the £85,000 turnover threshold has to count levy receipts, they could be forced into VAT, instantly slicing 20% from margins or pushing prices up further.

- Ripple effect on local spend: For a family staying two nights at £120/night, the levy adds £12. That might not sound like much — but it can mean skipping coffee and cake in a local café, or one fewer ticket at a small attraction. Multiply that by 580,000 overnight visits (Stirling & Forth Valley 2024 figure) and the ripple quickly matters.

What We believe Tourists Will Accept

Our experience working with small towns and businesses from and across Europe shows tourists are willing to pay levies if they see the benefit.

In fact, willingness to pay can increase threefold when funds are clearly tied to conservation or visible improvements.

A sign saying “Your levy helped repair this trail” is far more powerful than a vague assurance that it went into a council budget.

Signing a Smarter Levy for Scotland

Scotland has a chance to avoid repeating mistakes seen elsewhere. Three design changes could make ‘tourist taxes’ more effective and more acceptable:

- Local Hypothecation: Keep at least part of the revenue in the community where it was raised. If Callander visitors pay, Callander should see the benefits.

- Fair Burden Sharing: Consider including day-trippers, campervans, or even event tickets. Right now, the burden falls only on overnight guests.

- Protect Microbusinesses: Exempt levy receipts from VAT turnover thresholds, and offer support for small operators to absorb admin costs.

The Bigger Picture

Scotland is expensive compared to many European destinations, with a 20% VAT rate on accommodation. Adding a levy risks tipping some visitors toward cheaper destinations — or simply reducing what they spend once they arrive.

But done transparently, a levy could become a tool. Smoothing out seasonality, funding conservation, and ensuring communities actually benefit from the visitors who come to enjoy them.